The sounds of Berlin techno post-punk flood the railroad style apartment as a group of undergrads watch a freshly shaven leg get poked once, and then again. The setup is makeshift: a stool, the low hum of a tattoo gun, gloves. This kind of gathering occurs almost weekly. Last session’s black ink still sits on top of raw skin, not yet settled. For the students, this is a ritual. This is body modification.

Airplane tattoo done by Julia

Body modifications do not exist in a vacuum: often, they inform or respond to the mental state of young adults. We are predisposed to viewing people with body mods as other and unprincipled. In reality, these forms of self expression are growing more popular on and off campuses as a form of self expression and a way to address mental health. Colloquially dubbed ‘body mods,’ body modifications take on many a medium. With tattoos, hair dye, and piercings among the most notable, body mods can be used to buoy a low mental state, for aesthetic purposes, and, at other times, simply for fun. Most body mods require parental consent until the age of eighteen. Consequently, college is the first time students may freely shape their outsides to reflect their insides.

The negative connotations that come with tattoos and other body mods predate the judgment of college administrations by a longshot. Tattoos, piercings and hair dyes were used to convey certain messages for centuries. The earliest tattoos date back to 3300 BC and were discovered on mummies. In Ancient Greece and Rome, criminals were sentenced to a tattoo detailing the crime they committed as punishment for their actions. Later on, inmates modified their bodies to express ranking, or to affiliate with gangs. Oftentimes, the underground body mods we see prevalent in Western society are co-opted from indigenous cultures. This is evident in the Maasai tribe’s neotribalist use of stretched earlobes and body scars, for example, or in the 4th century Samhan period: Japanese and Korean folklore has it that tattoos were used to signal comradery between humans and sea monsters. Sea monsters saw depictions of themselves on divers and fishermen’s bodies, and left them at peace. These images— large fish, or fire-breathing dragons — are popular motifs to this day. Modifications are borrowed and, in time, change in meaning.

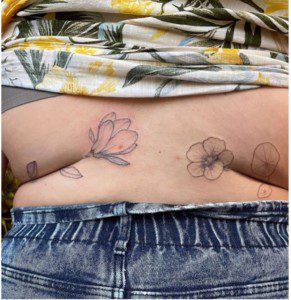

Flower tattoo done by Julia

As the use of body modifications evolves, so do the communities that practice them. College students are some of the most ardent participants in body mod culture. Texas State University authors Hill, Ogletree and McCray conducted a study which states that as momentum gains, “fewer differences between college students with and without tattoos will be found.” They go on to posit that “tattoos may be one mode of expressing individuality rather than a connotation of deviance.” This is a common theme: A 2012 central European test revealed that individuals with tattoos expressed stronger needs for uniqueness and sensation seeking. Doctor Broniarczyk-Dyla and professors Pajor and Switalska corroborate these findings in a 2015 study; though examining a wider range of ages, they confirmed that those with body mods have a higher demand for stimulation, i.e., sensation seeking.

Those with mental disorders often express that same tactile need. In fact, there is a whole school of therapy dedicated to treating urges related to sensation seeking. DBT, or Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, helps de-escalate those with mental disorders when their autonomic nervous systems encourage them to engage in dangerous behaviors. Skills that range all the way from cold showers to breathing techniques take brains from the heightened sympathetic state, back down to the grounded parasympathetic.

“The Sun” tattoo by Julia

Recent graduate of UMass Amherst, Julia Suh, is a trauma informed tattoo artist who believes tattooing can hold positive mental health effects. The majority of their clients are college students. “Everyone holds trauma in their body differently,” they stated. “The more I read about [trauma informed tattooing] the more I realized it’s something that should be ingrained in all forms of body work.” Julia, a proudly Korean artist, practices this not only in their physical approach to tattooing, but in their policy when booking appointments, too: they offer discounted or free work to those looking to cover up self-harm scars. In doing so, Julia is beautifying the scars of the past, and empowering young people to reclaim their bodies.

“There’s so few things I feel I have control over, but my body is one of them.”

Asked to recall a time tattooing felt healing in their own body, Julia brought up a harrowing event that transpired in the summer of 2021: “The day I heard eight Korean women were killed in Atlanta, I was so shocked. I immediately turned to tattooing. I tattooed this [traditional] fan on my leg while playing Korean folk music. I was in such a flow state, I didn’t realize time was passing. It felt so incredibly healing.” What Julia described is not uncommon; Judith Holland Sarnecki’s Trauma and Tattoo suggests the autotherapeutic healing power tattooing lends, as does Kasten E.’s German piece on body mods. Kasten E. suggests that, much like DBT, tattooing is a healthy coping mechanism young adults may use in place of self-harm. Even the aforementioned mummies from centuries past knew it: it was speculated they tattooed for the medicinal properties akin to acupuncture.

Toula, another recent graduate, treats their shaved head as a canvas and uses it as a transient medium: it grows out every few weeks. They said, “Whenever the world is just out of control, I’m like, “What if I bleached my head and eyebrows today? What if I got another piercing? What if I got a shoddy tattoo for no reason?” And there’s so few things I feel I have control over, but my body is one of them.”

Nowa R.’s Psychologiczne aspekty tatuowania się cites one of the main tiers of body mods as “desiring motifs associated with group membership.” These eccentricities are the building blocks of communities queer young folks seek out. Toula does this with their hair when they are stopped in the grocery store, or with their piercings on campus. “Chosen family has kept me off the streets and kept me fed and housed,” they said. “It’s so important, specifically because it’s not uncommon to lack biological family [in the queer community]. I don’t really have a biological family anymore so…chosen family means a lot to me.”Body mods also serve to create community through shared signs and images. This is particularly true for marginalized and vulnerable communities formed from the absence or rejection of other communities, as was the case with Toula. For a long time, Toula hid their identity from their family. When they came out as queer, the reaction was hurtful and alienating. Certainly, they were not alone and Toula says it is why queer signaling through hairstyles, piercings, and tattoos is such a potent act. It creates a sense of belonging, of identity.

Pictured above, Toula

These piercings, tattoos and subcultural hairdos can be off putting. At times, they’re even downright scary. But what is important to remember is that body modifying is an act of self expression and at other times, a misnomer; a red herring to deflect. Students that look the toughest on the outside often are softest on the inside.

Return to the students gathered in the apartment. By now, the music has died down. People are growing sleepy, curling up in corners with haphazardly thrown jackets as blankets. They’ve finished tattooing. The space is calm… that is, of course, until next time.

References

Hill, Brittany M., et al. Body Modifications in College Students: Considering Gender … https://gato-docs.its.txstate.edu/jcr:107936e2-8bde-427c-be55-dabec347edaa/Body%20modifications%20in%20College%20Students.pdf.

Pajor, Anna J., et al. Satisfaction with Life, Self-Esteem … – Psychiatria Polska. http://psychiatriapolska.pl/uploads/images/PP_3_2015/ENGver559Pajor_PsychiatrPol2015v49i3.pdf.

Pitts, Victoria. Visibly Queer: Body Technologies and Sexual Politics – JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4121386.

Glietsch, Friederike. “Korean Tattoo Culture.” An Historical Overview on the Development and Shift of Perception on Tattoos in Korean Society, 2020, https://doi.org/http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1454985/FULLTEXT01.pdf.