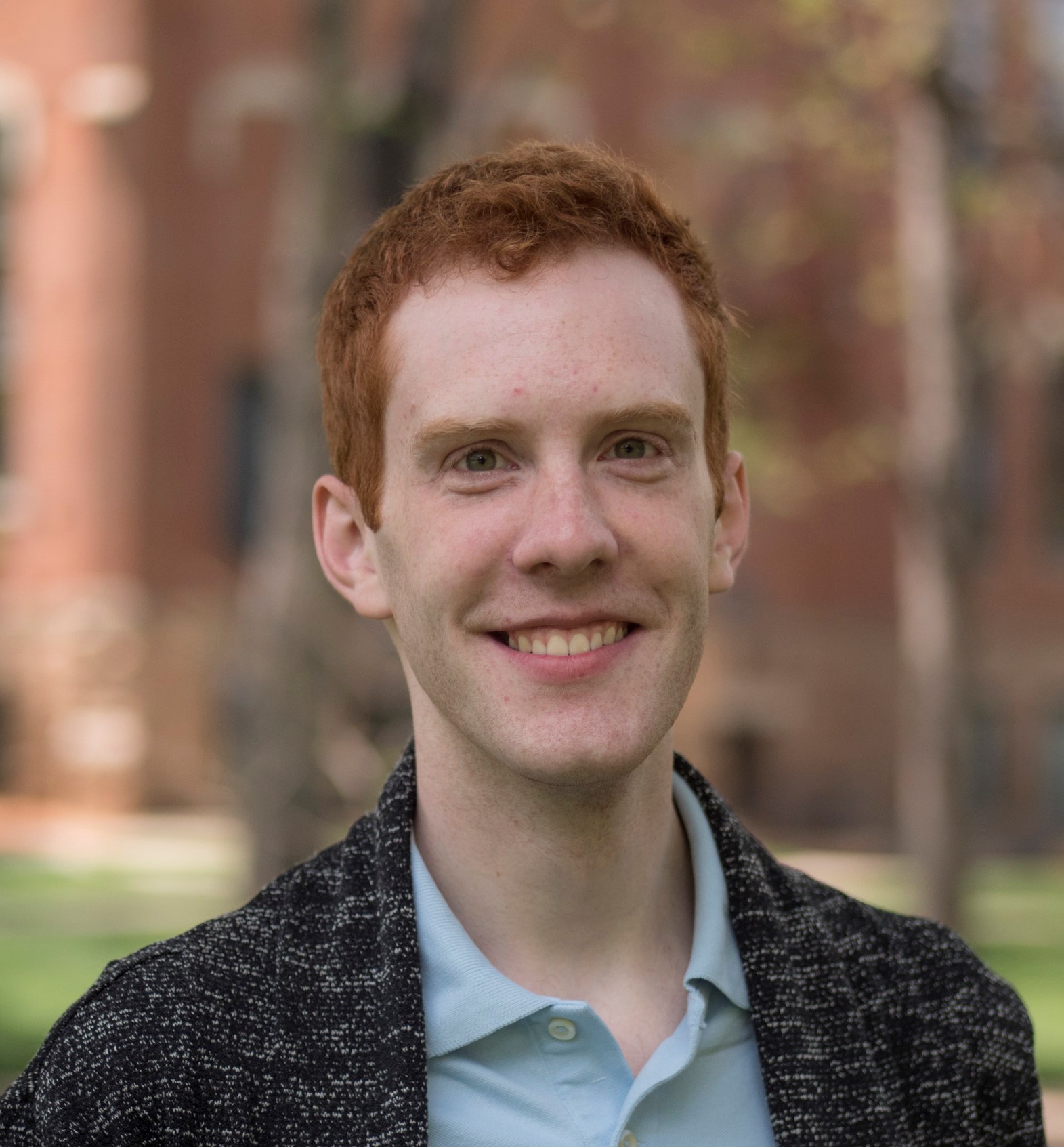

In talking with Brendan Griffiths, it is clear he chose the right profession. A Student Success Manager at Worchester Polytechnic University, Griffiths describes his role with doctoral students as “academic life coaching,” in which he supports students with their scholarly development, but also in their work-life balance and “all the parts of their lives that are relevant to them being a student,” addressing issues such as procrastination and time management. Griffiths says, “At the end of the day, when you’re a person who’s in school, you can’t fully separate your school life from the rest of your life. At some point, we have to recognize that sleeping and eating habits impact how you perform productively.” He also works on bigger picture concerns with students, addressing questions like, “What do I want to do with my life after I get this degree?” Griffiths is contagiously enthusiastic about his role as a coach and is an effective proselytizer for the practice itself – calling his job fun, exciting, challenging, interesting, and incredible.

There is growing interest in academic coaching programs, which have existed in higher education for about 20 years. A 2021 study found that an academic coaching program was associated with improved academic outcomes including increased GPA, retention, and semester credits. Griffiths points out that while there are education programs and certifications for coaching, no licensure is required to call yourself a coach and there is no certifying body. “If you say you’re a coach, you’re a coach.” Which leads to the question, what actually is a “Coach”?

Griffiths defines “coaching with a capital C” as “helping someone ask questions about themselves and then take action to respond.” Using tools like active listening (mirroring someone’s thoughts back to them), open-ended questioning, and goal setting, the job of a coach is to explore an issue a person is having to help them better understand it and where its’ coming from, and then to move into an action state.

What distinguishes coaching from other realms of support is its action-oriented philosophy, or the intention to change behavior. Griffiths’ coaching sessions end with questions like, “How are you going to experiment with changing your behavior in the next few weeks?” or “What could you start doing to get out of your own way?”

Griffiths explains that a fundamental philosophy of coaching comes from the assumption that you cannot give effective advice without having the lived experience of the person you are trying to help. So, Griffiths says, “That becomes the interesting tension. How do you present options and give people a sample platter of different ideas while also allowing them to make them their own choice? As in, “You’re the only person who knows enough about what you’ve done and what works and doesn’t work for you to personalize this thing to make it individualized.” A coach to his core, Griffiths’ responses are peppered with questions, and he reflexively adds “Right?” to the ends of his sentences, checking to see if I’m following.

As an undergraduate, Griffiths studied chemistry and music. He went on to a PhD program in chemistry at the University of Colorado, calling it the “expedient choice,” believing there were more job prospects in teaching chemistry than in conducting choirs. “Spoiler alert. That was not the best choice for me,” he says, which he realized halfway through his doctoral program, leaving with a master’s instead and eventually leaving that path entirely. After completing his master’s, Griffiths became an advisor for chemistry and biochemistry major at CU, and he learned that while advising is focused on giving directive guidance, he really loved the meandering conversations that were part of the process, often having little obvious connection to the problem at hand. He also saw the benefit of CU’s academic coaching program on some of the students he was advising. “The students that I referred to them were coming back and saying, ‘Oh my God, it was so amazing. We got to talk about my life and my family and what I want to do and all these things.’ And I am like, ‘Wow, that’s incredible.’” So, as soon as he was able, Griffiths transferred to the academic coaching program.

What distinguishes coaching from other realms of support is its action-oriented philosophy, or the intention to change behavior.

It is easy to recognize the parallels to Griffiths’ own academic experience when he talks about how coaching can help students make more informed decisions about their academic and post-graduate lives. He sees them, too. “I love this work so much because it’s really fun,” he says. “But also because this is exactly what I needed when I was a grad student.”

Griffiths describes coaching as a process, so he usually aims for at least four sessions “as a starting point.” Through that process, Griffiths and the students he coaches set actionable goals during each session and check back in the next time they meet. Over time, they can recognize patterns in behavior, where certain issues – like procrastination – keep coming back, despite attempts to take action to change them. “There ends up being a big story arc, right?” says Griffiths. After he has done enough work with a student, they can do a “meta-level check in” where he can ask, “What have you been learning about yourself through all of these experiments?” Students end up with a better understanding about how they operate and how they don’t, which can offer a deeper insight into how to live and work better.

The topic of mental health comes up frequently in Griffiths’ sessions, but not always directly. (WPI has tragically experienced several student suicides over the past two years). “Students come to coaches when they want to make a change,” Griffiths says. “I have found that people come to coaching and they have, I like to call it the ‘presenting agenda’ or the ‘surface agenda’ – like ‘I’m procrastinating a lot.’ And when you start exploring that with them, it turns out they aren’t sleeping or maybe they say they’re depressed.” Griffiths acknowledges the limits of his role in that conversation but tries to help where and when he can. “I’m not a therapist, I’m not a mental health professional. And I want to be extra cautious of not presenting myself as an expert,” he says. “At the same time, I don’t want to take a hot potato approach and say we’re not allowed to acknowledge that you’re struggling.” Griffiths believes coaching can be a first step for many people, especially for those who feel there is a stigma associated with getting mental health support. “It’s a place where people can develop enough safety with a person to recognize that they’re not doing as well as they were pretending, which is often the first step for people to make change.”

Griffiths also recognizes a cultural tendency in higher education to “pathologize issues that don’t always need to be approached from a clinical direction” and jump right to therapy whenever there is an implication of a mental health challenge. “There’s validity to that. But it can also be a very kind of shutting down sort of response. I think there’s value in coaching’s approach of being able to give somebody the space to acknowledge they are struggling and consider taking action.” Griffiths also finds that some students need a bit of “space and breathing room” to come to the decision to seek therapy in their own time, without feeling pressured to go right away.

Whether it’s time management, scheduling or something more personal that is getting in the way, Griffiths says with conviction, “All of us need a coach at one point in our lives.”