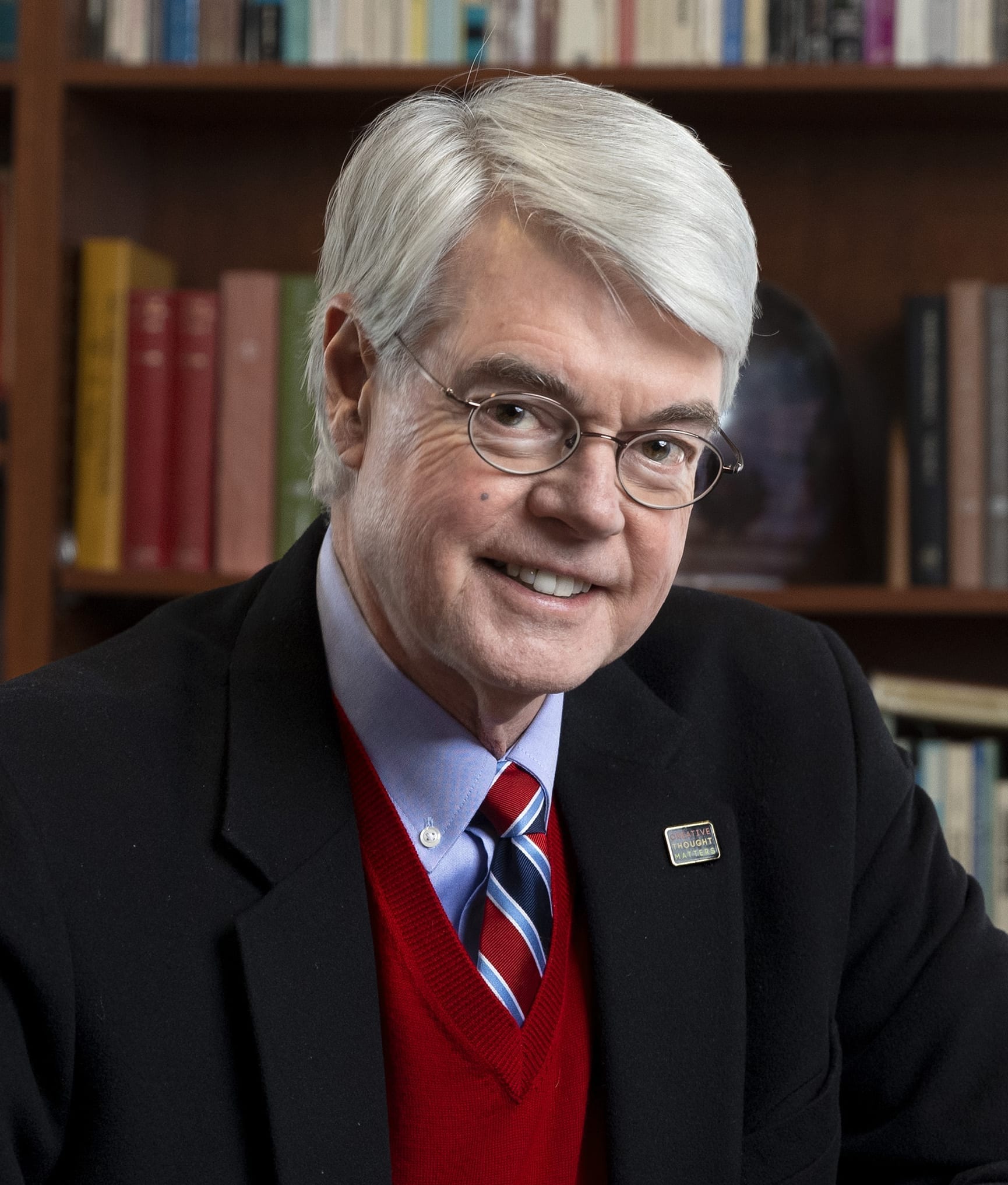

Philip Glotzbach has been president of Skidmore College for the last 17 years, a period in which the idyllic school in upstate New York has changed significantly – as has higher education overall.

Founded in the early 20th century as an institution for women hoping to gain self-sustaining professional and personal skills, Skidmore has held onto its social justice roots through its co-ed transition in 1971 and its rise to prominence as a prestigious, liberal arts college in one of the most beautiful college towns in America.

Skidmore now has 2,500 students from 40 states and 70 countries on its residential campus located just outside of the main thoroughfare of the resort town of Saratoga Springs.

Newsweek called Skidmore “A New Ivy,” others have included it among the Hidden Ivies. Glotzbach may prefer to think of it as a college of the future, set on continuing its path to greater diversity and preparing students for careers not yet imagined. While acknowledging a general shift toward job-specific degrees and transactional compacts between students and institutions, Glotzbach is a fierce defender of the higher purpose of higher education – to produce thoughtful participants in civic life.

When it comes to student behavioral health and wellbeing, Glotzbach has much to offer by way of both observation and experience. Like many schools, Skidmore is trying new models in mental health service delivery in order to keep up with student demand.

But Glotzbach believes service innovation represents only one approach to a much larger issue of young-adult wellbeing influenced by societal trends, family dynamics, and pressures springing from the rapid changes of the new century.

Glotzbach is retiring in June, moving on from Skidmore to pursue writing projects dealing with higher education’s impact on democracy and the role of “citizen intellectuals.” He deflects talk of his legacy, saying humbly that “college presidents are often credited with the accomplishments of others.” Still, he has plenty of insight about the role of leadership in helping students navigate a changing, complex world.

We talked by phone in January of 2020.

Mary Christie Quarterly: When you look back at your time at Skidmore, what are some of the biggest changes that have occurred on campus?

Philip Glotzbach: When I first came to Skidmore, I was very attracted by our motto, “Creative Thought Matters.” I think that phrase epitomizes so much of what was true of Skidmore in the past and I hope is even more so today.

The most obvious, and I would say positive, change is that we are a much more diverse college. Students of color now make up around 25% of our population; international students number approximately 11%. We also have increased our socio-economic diversity, which is reflected in our most recent entering class – about 17% first-generation and about the same number Pell grant-eligible students.

So, our incoming classes are increasingly more diverse and also better academically prepared – the result is we have a stronger, more vital, and more interesting student body. But it’s not just the students. We have created what has become a national model in faculty hiring for increased diversity. In fact, we have made strides in diversifying our whole community, which has benefitted us in so many ways, including our competitiveness.

One big change that we implemented, which has helped all our students succeed, is our first-year seminar program. Every first-year student enrolls in a first-year seminar – classes that are taught by full-time faculty members of all disciplines. These professors become the students’ mentors and academic advisors, typically for the first year, sometimes for the first two years, sometimes forever. We expect our first-year faculty members to get to know their students and to work with them on their academic choices – not just picking their next semester’s classes, but thinking about their values, their goals, what they want to achieve and, if they hit roadblocks, what resources are available to them.

Physically, our campus also has changed dramatically since I arrived. We are working right now on the largest single building project in the history of the college – our Center for Integrated Sciences that will bring together all of the departments and programs in the physical and life sciences. I’m very pleased about that (you know presidents love to build things).

The other major change I would say is in our governance structure. There are a lot of silos in higher ed that are just not productive. At the beginning of every semester, we bring together the chairs of major committees and members of the Presidents’ Cabinet, and we just talk through our agendas for the coming term. When you do that, everyone has the benefit of knowing what everyone else is doing, and it reduces the number of surprises that can lead to misunderstanding, friction, and resentment.

MCQ: How much of your governance work involves setting the right tone as president?

PG: I try to bring my best self to these conversations. I don’t always succeed, but I do think there is a value in being consistent over time in trying to lead from a place that reflects the better angels of our nature.

MCQ: What has been your experience at Skidmore in terms of student behavioral health?

PG: Like all of the institutions I’ve spoken with, we’re experiencing an increase in both the issues we see in students and in the demands for service that they request. There are more students reporting anxiety; more reporting depression.

MCQ: What has been your response?

PG: We certainly have added staff to our Counseling Center and in other areas as well. But in regards to capacity for meeting the increased demand, I do not believe it is possible to build your way out of the current demand.

An analogy is the congested freeways of Los Angeles. The response there has been to build another lane. And as soon as it’s open, the freeway is just as congested as before, with even more cars on the road. I think that’s what we’ve been seeing on college campuses with respect to counseling centers. The first call has been to add more counselors to increase capacity, and then that enhanced capacity is very quickly exhausted.

I think the answer in the long run has to be in exploring different models for meeting students’ needs. We are working with a new model we call our ‘step system’, which really tries to change what happens when students first come to the Counseling Center. Instead of the counselor automatically saying, “let’s set you up with a series of appointments,” they sit down with the student and come to a mutual understanding of what that student is dealing with and then review the resources that are available to them. The expected outcome of that first meeting is a plan the student will execute over the next few days or weeks.

The underlying understanding here is that, number one, students have to take responsibility for their own health and wellness and, number two, where we can provide resources, we need to do it in more than just one place.

In fact, we’re looking at engaging all members of the campus community in addressing student behavioral health. For example, our Director of Campus Spiritual Life is very involved in mindfulness work. We have a program called Peer Health Educators in which about 80 students work out of an office in the student center helping other students access resources and live in healthier ways.

We’re also working closely with faculty members, helping them understand when they need to refer a student to the counseling center and when they don’t. Faculty legitimately worry about legal obligations and self-protection, so we end up having people over-referring students to the counseling center. We’re not trying to turn our faculty members into counselors, but they do need to understand that just because a student is upset about something doesn’t mean that they need to go to counseling.

MCQ: Do you think students are different today?

PG: I do think students are different in many ways, and much of this comes from the milieu with which they were educated. College admission is much more competitive than it was fifteen years ago, so students became very high achieving in high school and put a lot of pressure on themselves to do as many things as possible.

Parents are different today as well, and there are a lot of reasons for that. They are very focused on positioning their student for success in the job market. The 2007 and 2008 recession really shook everybody up, and it convinced students and parents that there’s no guarantee to economic success after you graduate from college, even though you’ve just invested $250,000 or more in your college education. Students have high expectations for themselves as a result. They can feel under enormous pressure.

MCQ: Do you think college and universities are feeling the pressure to justify their link to the job market?

PG: I think every institution today acknowledges an obligation to justify itself relative to employment after college, and it’s a fair expectation. But at the same time, I think it’s very, very important for us, particularly for college presidents and people in leadership positions, to make it clear that the value of a liberal education in particular, and a college education in general, is not just about that first job.

I worry about the economic and social pressures parents and students feel to take a more narrow course of study that very directly prepares them for a particular job. Sometimes, the more narrowly focused your preparation, the shorter its shelf life – because if the field changes, you will not be prepared to change with it. The argument for the liberal arts has always been that a liberal education prepares you for the most important factor you are going to face in your life and that is change.

This reality puts a premium on the capacity to continue to learn, to think, to write, and to express yourself clearly. Increasingly with the issues that we’re facing in both our professional and political lives, you will need to be able to think across disciplinary boundaries. The big problems we face collectively as humanity – be it climate change or the coming industrial revolution based on AI, or the divisions in our political life – are not going to be solved by one specific disciplinary perspective. And, more than ever, creativity matters.

The other thing I would say is that, as colleges and universities justify themselves and what they are asking students and parents to pay, we have to get away from defining higher education as just a private good. It should be an articulated part of the mission of every college and university to prepare its graduates to participate effectively as citizens in a democracy. We need more informed, responsible citizens today than ever before, and the only way we’re going to do that is to educate more people about their responsibility as citizens. Part of our responsibility as a college is to help students understand that this education is not just for your personal benefit – it’s also for the benefit of the polity: your city, state, and country.

I have a concept that I’m exploring about educating citizen intellectuals – not necessarily someone in the world of letters but people who will draw upon what they have learned in college to approach their life thoughtfully, to understand that their opinions matter and that they should express them, and to think about making our civic life better.

MCQ: What are you looking forward to working on now that you are close to retiring?

PG: I’ve spent over 40 years in higher education, and I think when one retires from a position like this it’s important to retire to something. I have a number of writing projects I’m working on – one is a book about higher education and democracy: What are the things that colleges and universities can do to be more intentional about educating those informed, responsible citizens I was referring to?