Innovations in Behavioral Health Care is a peer-reviewed section of the Mary Christie Quarterly that features breakthrough research and commentary on the emotional and behavioral health of young adults.

Malinda Kennedy, ScD is a Project Director for the Maryland Collaborative and Faculty Assistant for the Center on Young Adult Health and Development, University of Maryland School of Public Health, College Park, MD

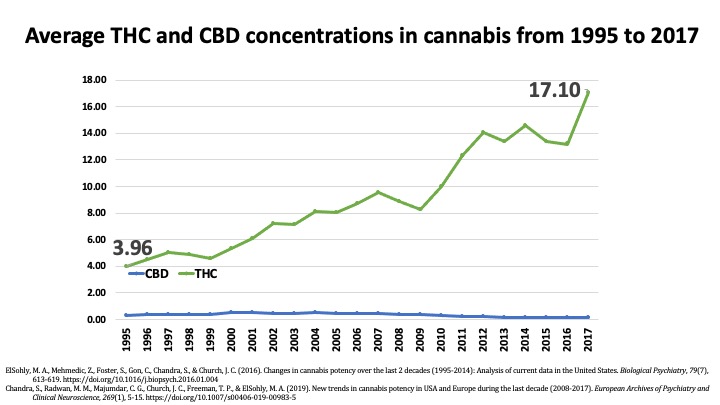

Figure 1

Cannabis use during the past year has increased among college students to 44%, its highest point since 1983, with a quarter of college students using cannabis during the past month (Schulenberg et al., 2021). Meanwhile, nationally, young adults’ perception of harm from cannabis use is at its lowest point since 1980 (Schulenberg et al., 2021). As the perception of harm from cannabis use has decreased, the potency of cannabis has increased substantially during the past several decades. As seen in Figure 1, the average amount of THC, the psychoactive component that gets a person “high,” has increased dramatically. Today, the average amount of THC in cannabis plants is roughly 17%, but cannabis products can contain 40% to 80% THC (Chandra et al., 2019; ElSohly et al., 2016; Sagar et al., 2018). This is a very different product from the average 4% THC cannabis of the 1990s (ElSohly et al., 2016).

This combination of increased potency, increased use among young adults, and decreased perception of harm is particularly relevant for institutions of higher education. Studies have repeatedly found that academic achievement is hindered by cannabis use, and the risk for negative outcomes increases with higher potency and increased frequency of use (Arria et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2002; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2019; Suerken et al., 2016; Wilhite et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2018).

The movement to legalize cannabis and the ubiquitous promotion of cannabis has paralleled these changes in perceptions of safety and, anecdotally, many believe that if these products are available, they must be regulated and safe. In fact, consumers of cannabis cannot always be confident about either the content or the strength of their cannabis product. Many are unaware that the cannabis landscape is very different today than it was 30 years ago, both in terms of the product itself and its availability. Information regarding adverse effects of cannabis is not widely known and has been overwhelmed by pro-cannabis marketing. As cannabis products have become increasingly available, the proliferation of pro-cannabis messaging has grown and can be found everywhere from Pinterest to highway billboards.

During the past several years, data from the Maryland Collaborative to Reduce College Drinking and Related Problems indicate that college students increasingly have misinformed beliefs related to the potential harms from cannabis use. The variety of misperceptions about cannabis use include that it is not addictive, that it can be an effective way to reduce stress, and that it can improve mental health. All of these beliefs are at odds with research evidence, but college students are often not receiving their health information from credible, research-based sources. Adolescents and college students who think cannabis is less harmful or are unaware of potential harms, and those who have been exposed to pro-cannabis information are more likely to use cannabis (Cabrera-Nguyen et al., 2016; Roditis et al., 2016).

Information regarding adverse effects of cannabis is not widely known and has been overwhelmed by pro-cannabis marketing.

Today’s college students have unprecedented access to information, but many of the sources of health-related information are secondary sources, including opinion pieces. When it was more common for information to flow through traditional news outlets and institutions, there were established routines and reviews to evaluate the accuracy of information before it was widely disseminated. These guardrails are no longer in place in the current media environment. Technology has leveled the information playing field to the point where true and false information are not only equally available, but false information is often easier to find and more widely available. Even if people are not convinced by false information, the presence of so much contradictory information can sow seeds of doubt about what and whom to believe.

In July 2021, the U.S. Surgeon General released an advisory report on confronting health misinformation due to concerns regarding the large amount and rapid spread of misinformation on a wide range of health conditions (Office of the Surgeon General, 2021). This misinformation is characterized by false facts that spread quickly via social media formats and traditional social networks such as families, co-workers, and friends. Studies of health information have found Twitter to be a leading platform of health misinformation (Suarez-Lledo & Alvarez-Galvez, 2021). In fact, false claims about cannabis are one of the most common topics of incorrect health information on Twitter (Suarez-Lledo & Alvarez-Galvez, 2021).

However, misinformation can be found on all social media platforms. People who find their information about cannabis from the Internet or social media have been more likely to believe unsupported claims about cannabis (Ishida et al., 2020). These falsehoods tend to spread faster than truths and it is estimated that true information can take six times longer to reach people than false information (Vosoughi et al., 2018). False information can be either intentionally spread (disinformation) or unintentionally spread by people who do not realize the information is false (misinformation), but as it was once said, a lie told often enough becomes the truth.

It might be a surprise to learn that a person’s susceptibility to misinformation is not related to their intelligence. Our own brain wiring sets us up to be tricked. For starters, our brains typically code new information as true. Compound that with the fact that the more we see the same information, and if that information fits our existing attitudes, beliefs, and expectations, we are also more likely to believe it. So, we have an inherent vulnerability to believing misinformation—simply, it is quite easy for us to fool ourselves (Southwell et al., 2017).

A deep dive into the work of experts studying misinformation revealed recommended solutions that might be useful to apply in our efforts to help students. Interventions to stop the spread of misinformation can either target the structural level by reducing the amount of misinformation seen on platforms or target the individual level through efforts to increase individuals’ resistance to misinformation (Lazer et al., 2018). For institutions of higher education, working at the individual level with students to mitigate the impact of misinformation seems a natural fit. Colleges and universities have by default a gathering of experts from many disciplines who are accustomed to collaborating with each other to solve new societal challenges. However, professors well-versed in educating college students might be unsure how to undo the harmful false information that has permeated their campuses and the students’ consciousness. To help them, we can rely on research conducted on educational approaches to reduce misinformation and disinformation by professionals from a variety of disciplines, including political science, psychology, education, health literacy, and information technology.

Many of the effective strategies have shown promising results and boil down to the following key components: the general strategies of teaching digital literacy, “prebunking” and encouraging accuracy checks, and the course-specific strategies of teaching science literacy and health literacy. The goal of these strategies is to build resilience among students to make them resistant to misinformation and to minimize the chance they will unwittingly spread misinformation. These efforts are amenable to implementation in classrooms, educational forums, one-on-one sessions, or informal dialogues within units and across campus. Here are some specific recommendations:

General strategies

Teach digital literacy. Because college students’ main source of health information is the Internet (Kwan et al., 2019), colleges should consider teaching students how to evaluate Internet information. Even with this generation of college students’ increased digital knowledge, research indicates that students still struggle to assess the validity of digital content (Breakstone et al., 2021b; McGrew et al., 2018). There are updated digital literacy recommendations that students could be taught that are much more effective than older, now misguided, tips such as trusting a .org site more than a .com site. For example, a new strategy such as “lateral reading” is an effective and efficient way to help students evaluate online materials (Stanford University, 2022; Wineburg & McGrew, 2019). Lateral reading is a method used by professional fact checkers that involves moving from the original page and opening new pages to search for what other sites say about the content or author of the original page. This method is not only effective for evaluating the trustworthiness of the original site, but often takes less time. Students have been successfully taught these skills, often with brief interventions that are not time intensive (Breakstone et al., 2021a; McGrew, 2020; McGrew et al., 2019).

Encourage accuracy checks as a strategy that asks students, are you a misinformer? These checks ask students to pause and consider the veracity of online information before sharing it. Often, people share information they see while scrolling through social media in their downtime. In this relaxed state, accuracy is not foremost on their minds. Nudging students to think about the accuracy before sharing reduces the chances of sharing misinformation (Fazio, 2020; Pennycook et al., 2021).

Use prebunking as a warning measure. Like the traffic sign that warns you of a steep incline ahead, a prebunk warns of false information that might be soon encountered. Simply warning students of false information before they see it, explaining why it is false, and providing the correct information has been shown to build people’s resistance to that false information (Cook et al., 2017; Jolley & Douglas, 2017; van der Linden et al., 2017).

It is important to provide the corrective information as an alternative to the falsehood. Prebunking could be delivered through any medium but is best delivered by a trusted source.

Course-specific strategies

Teach science literacy. The deliberate thoroughness of the scientific process is actually a handicap in the fight against misinformation. Science proceeds with a rigorous and methodical purpose that is based in a set of methods and peer review. The scientific process takes time and the more rigorous the study, the more time it typically takes to complete. This is in exact opposition to non-scientific information which can be spread with the click of a button. This puts science at a disadvantage to misinformation where, with a single click, a person can wittingly or unwittingly post a falsehood to social media that could multiply exponentially before a scientist has finished drafting their proposal for a research study. This imbalance of information leaves science, regulators, and governments struggling to catch up with and refute the large amount of nonscientific information. It is critical for all students, not just those pursuing the sciences, to understand how the scientific process works and how to evaluate scientific from non-scientific information. This could be taught as a separate course or at a minimum it could be inserted as a science literacy lesson plan in a required science course.

Teach health literacy. Improving personal health literacy, the ability for people to find, understand, and use information and services to make well-informed, health-related decisions and actions, is included in the Healthy People 2030 goals (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2021), and teaching and improving health literacy at the college level through required annual coursework was recommended more than a decade ago in the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010). Although some institutions might struggle to add additional health literacy courses and instructors, incorporating the previously mentioned digital and science literacy skills into existing courses would strengthen students’ ability to find reliable information, including health information (Chen et al., 2018). Recognizing reliable sites for health-related information and understanding how to evaluate whether or not a site is trustworthy are critical skills for today’s students to learn. If an independent health literacy curriculum is not possible, at least imbedding some of these digital literacy skills within existing lesson plans of other courses could still improve students’ personal health literacy skills.

Higher education professionals should maximize opportunities to tackle the infodemic of cannabis misinformation. Building student resilience against any type of misinformation they might encounter by teaching health literacy skills is not an unrealistic goal. A discussion of the need to address the gap in digital literacy has been previously brought up to institutions of higher education (Supiano, 2019). For institutions facing constraints, there are many readily available “plug and play” materials developed by researchers and organizations related to accuracy nudges; prebunking; and digital, science, and health literacy, and many are free. Institutions of higher education frequently require students to watch certain online trainings as part of first year programming. Online digital literacy training could be added to this list of requirements with minimal cost, and support for the use of institutional resources to implement it could be bolstered by promoting it as central to the academic aims of a college education. Just including accuracy nudges and reminders in relevant online messaging, such as campus announcements, social media posts, and daily news emails could at least reduce the spread of misinformation.

With new technology comes new risks and prevention professionals usually have to play catch up to address these risks. The increased availability of cannabis products and marketing will continue to impact college students and threaten some students’ path to academic success. Colleges and universities are places of innovation and collaboration and by working together they can strengthen students’ resilience to cannabis misinformation, by including skills training in new courses, as embedded sections of current courses, as part of first year trainings, or in regular campus messaging. Colleges and universities are ideal places to invest in teaching students the foundational skills they need to protect themselves from misinformation. As with many health concerns, prevention is more efficient than trying to cure afterwards. This health infodemic of cannabis misinformation reminds us of the fable of the tortoise and the hare. Facts are currently the tortoise and misinformation is the hare. But as with the fable, in the end, with the help of the campus community, the slow and steady facts will win the race.

References

Arria, A. M., Barrall, A. L., Allen, H. K., Bugbee, B. A., & Vincent, K. B. (2018). The academic opportunity costs of substance use and untreated mental health concerns among college students. In M. D. Cimini & E. M. Rivero (Eds.), Promoting Behavioral Health and Reducing Risk Among College Students: A Comprehensive Approach (pp. 3-22). Routledge.

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Connors, P., Ortega, T., Kerr, D., & Wineburg, S. (2021a). Lateral reading: College students learn to critically evaluate internet sources in an online course. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 2(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-56

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Wineburg, S., Rapaport, A., Carle, J., Garland, M., & Saavedra, A. (2021b). Students’ civic online reasoning: A national portrait. Educational Researcher, 50(8), 505-515. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211017495

Cabrera-Nguyen, E. P., Cavazos-Rehg, P., Krauss, M., Bierut, L. J., & Moreno, M. A. (2016). Young adults’ exposure to alcohol- and marijuana-related content on twitter. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77(2), 349-353. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2016.77.349

Chandra, S., Radwan, M. M., Majumdar, C. G., Church, J. C., Freeman, T. P., & ElSohly, M. A. (2019). New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008-2017). European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 269(1), 5-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-00983-5

Chen, C. Y., Wagner, F. A., & Anthony, J. C. (2002). Marijuana use and the risk of major depressive episode. Epidemiological evidence from the United States National Comorbidity Survey. Social Psychiatry And Psychiatric Epidemiology, 37(5), 199-206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-002-0541-z

Chen, X., Hay, J. L., Waters, E. A., Kiviniemi, M. T., Biddle, C., Schofield, E., Li, Y., Kaphingst, K., & Orom, H. (2018). Health literacy and use and trust in health information. Journal Of Health Communication, 23(8), 724-734. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2018.1511658

Cook, J., Lewandowsky, S., & Ecker, U. K. H. (2017). Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PLoS One, 12(5), e0175799. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175799

ElSohly, M. A., Mehmedic, Z., Foster, S., Gon, C., Chandra, S., & Church, J. C. (2016). Changes in cannabis potency over the last 2 decades (1995-2014): Analysis of current data in the United States. Biological Psychiatry, 79(7), 613-619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.01.004

Fazio, L. K. (2020). Pausing to consider why a headline is true or false can help reduce the sharing of false news. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(2), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-009

Ishida, J. H., Zhang, A. J., Steigerwald, S., Cohen, B. E., Vali, M., & Keyhani, S. (2020). Sources of information and beliefs about the health effects of marijuana. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(1), 153-159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05335-6

Jolley, D., & Douglas, K. M. (2017). Prevention is better than cure: Addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47(8), 459-469. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12453

Kwan, G., Shaw, J. A., & Murnane, L. (2019). Internet usage within healthcare: How college students use the internet to obtain health information. Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet, 23(4), 366-377. https://doi.org/10.1080/15398285.2019.1681247

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094-1096. https://doi.org/doi:10.1126/science.aao2998

McGrew, S. (2020). Learning to evaluate: An intervention in civic online reasoning. Computers & Education, 145, 103711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103711

McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., Ortega, T., Smith, M., & Wineburg, S. (2018). Can students evaluate online sources? Learning from assessments of civic online reasoning. Theory and Research in Social Education, 46(2), 165-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2017.1416320

McGrew, S., Smith, M., Breakstone, J., Ortega, T., & Wineburg, S. (2019). Improving university students’ web savvy: An intervention study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 485-500. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12279

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2019). Marijuana DrugFacts. National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institutes of Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved March 15 from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2010). National action plan to improve health literacy. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Health_Literacy_Action_Plan.pdf

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2021). Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved March 28 from https://health.gov/our-work/national-health-initiatives/healthy-people/healthy-people-2030/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030

Office of the Surgeon General. (2021). Confronting health misinformation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory on building a healthy information environment. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-misinformation-advisory.pdf

Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A. A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature, 592, 590-595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03344-2

Roditis, M. L., Delucchi, K., Chang, A., & Halpern-Felsher, B. (2016). Perceptions of social norms and exposure to pro-marijuana messages are associated with adolescent marijuana use. Preventive Medicine, 93, 171-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.013

Sagar, K. A., Lambros, A. M., Dahlgren, M. K., Smith, R. T., & Gruber, S. A. (2018). Made from concentrate? A national web survey assessing dab use in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 190, 133-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.022

Schulenberg, J. E., Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Miech, R. A., & Patrick, M. E. (2021). Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2012: Volume 2, college students and adults ages 19–60. Institute for Social Research: The University of Michigan. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2020.pdf

Southwell, B. G., Thorson, E. A., & Sheble, L. (2017). The persistence and peril of misinformation. American Scientist, 105(6), 372-. https://doi.org/10.1511/2017.105.6.372

Stanford University. (2022). Civic Online Reasoning: Intro to Lateral Reading. Retrieved March 15 from https://cor.stanford.edu/curriculum/lessons/intro-to-lateral-reading

Suarez-Lledo, V., & Alvarez-Galvez, J. (2021). Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(1), e17187. https://doi.org/10.2196/17187

Suerken, C. K., Reboussin, B. A., Egan, K. L., Sutfin, E. L., Wagoner, K. G., Spangler, J., & Wolfson, M. (2016). Marijuana use trajectories and academic outcomes among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162, 137-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.041

Supiano, B. (2019). Students fall for misinformation online. Is teaching them to read like fact checkers the solution? The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/students-fall-for-misinformation-online-is-teaching-them-to-read-like-fact-checkers-the-solution/

van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Rosenthal, S., & Maibach, E. (2017). Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Global Challenges, 1(2), 1600008. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.201600008

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151. https://doi.org/doi:10.1126/science.aap9559

Wilhite, E. R., Ashenhurst, J. R., Marino, E. N., & Fromme, K. (2017). Freshman year alcohol and marijuana use prospectively predict time to college graduation and subsequent adult roles and independence. Journal of American College Health, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2017.1341892

Wilson, J., Freeman, T. P., & Mackie, C. J. (2018). Effects of increasing cannabis potency on adolescent health. The Lancet. Child and Adolescent health, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30342-0

Wineburg, S., & McGrew, S. (2019). Lateral reading and the nature of expertise: Reading less and learning more when evaluating digital information. Teachers College Record, 121, 110302. https://purl.stanford.edu/yk133ht8603