Amanda Fowler had been trying to do college the right way. During her first months at the University at Albany in 2019, the 18-year-old threw herself into parties that reminded her of those she’d seen on social media—ones that promised to secure her the most desirable college experience. As she struggled to take care of herself at the same time, peers reassured her with a common refrain: partying and drinking aren’t an issue, they told her, until after graduation. She believed them at first, then started questioning their collective priorities. “I actually don’t think that’s how that works,” she remembered deciding. “We might have a problem.”

Though skeptical of her community’s attitude toward substance use, Amanda was willing to wager she’d find a way out of it by looking inward. When she returned the second semester, she applied to volunteer with UAlbany’s Middle Earth Peer Assistance Program hotline. She joined a Collegiate Recovery Program, designed to support students grappling with their own relationship to drugs and alcohol or that of people close to them. She switched her major from cybersecurity to psychology. Whatever the pervasive mindset on campus, she found pockets of other students interested in pursuing a happier lifestyle and helping each other in the process.

For Amanda, turning to a peer community that was supportive and relatable changed the course of her college experience, and likely her life. But despite these individual success stories, peer support programs, in the aggregate, continue to raise concerns among administrators who are often hesitant to embrace them. That’s why, in November 2022, the Mary Christie Institute (MCI), commissioned by the Ruderman Family Foundation, published a white paper to examine peer support practices in the college setting. The paper affirms the need for peer support as part of a public health solution to student mental health, but also calls for new research and regulations to secure and strengthen the field going forward.

“Our goals with the white paper were to provide the field with information that can help guide policy and program decisions and provide student leaders interested in peer support with information on comparative programs and lessons learned,” Dr. Zoe Ragouzeos, one of the authors and MCI’s clinical director, said during a webinar to review the report in November 2022. The other authors are MCI executive director, Marjorie Malpiede, and associate director, Dana Humphrey.

While peer support programs first emerged decades ago, they’re becoming increasingly common in the face of a mounting youth mental health crisis, MCI’s paper explains. As more students than ever before report experiencing mental health issues, demand for college counseling services is soaring. Particularly since the pandemic left young people reeling both socially and emotionally, traditional counseling departments are finding themselves without enough staff to meet all the need. This strain on clinical support has pushed community members to think creatively about other ways to fill in the cracks, including by calling on students for help.

“For Amanda, turning to a peer community that was supportive and relatable changed the course of her college experience, and likely her life.”

The adoption of peer support on college campuses does not happen lightly, though. Enlisting students as mental health providers comes with risks, given that volunteers receive varying degrees of training and are not operating in a professional capacity. In the summer of 2022, MCI conducted a survey of counseling center directors and found “near-universal interest (95%) in some type of peer support program.” At the same time, the vast majority reported believing that personal risk to students providing peer support (98%), personal risk to students receiving peer support (96%), and risk to the institution (93%) were important concerns.

Through a review of existing research on peer support, interviews with experts in the field and case studies on individual programs, the benefits of college peer support crystallized. One of the programs featured is UAlbany’s Middle Earth Peer Assistance Program, where Amanda Fowler, now a senior, serves as recruitment chair. Dubbed by MCI as “the standard bearer in college student mental health peer support,” Middle Earth offers a decades-old peer support hotline, as well as peer coaching and education services. Dr. Dolores Cimini, the former director, suggests colleges have an obligation to help train college students to deal with mental health concerns. “They provide vital services to their fellow students,” she said during the November 2022 webinar. “It’s very clear that the first individuals that [students] would reach out to when they are struggling is their peers.”

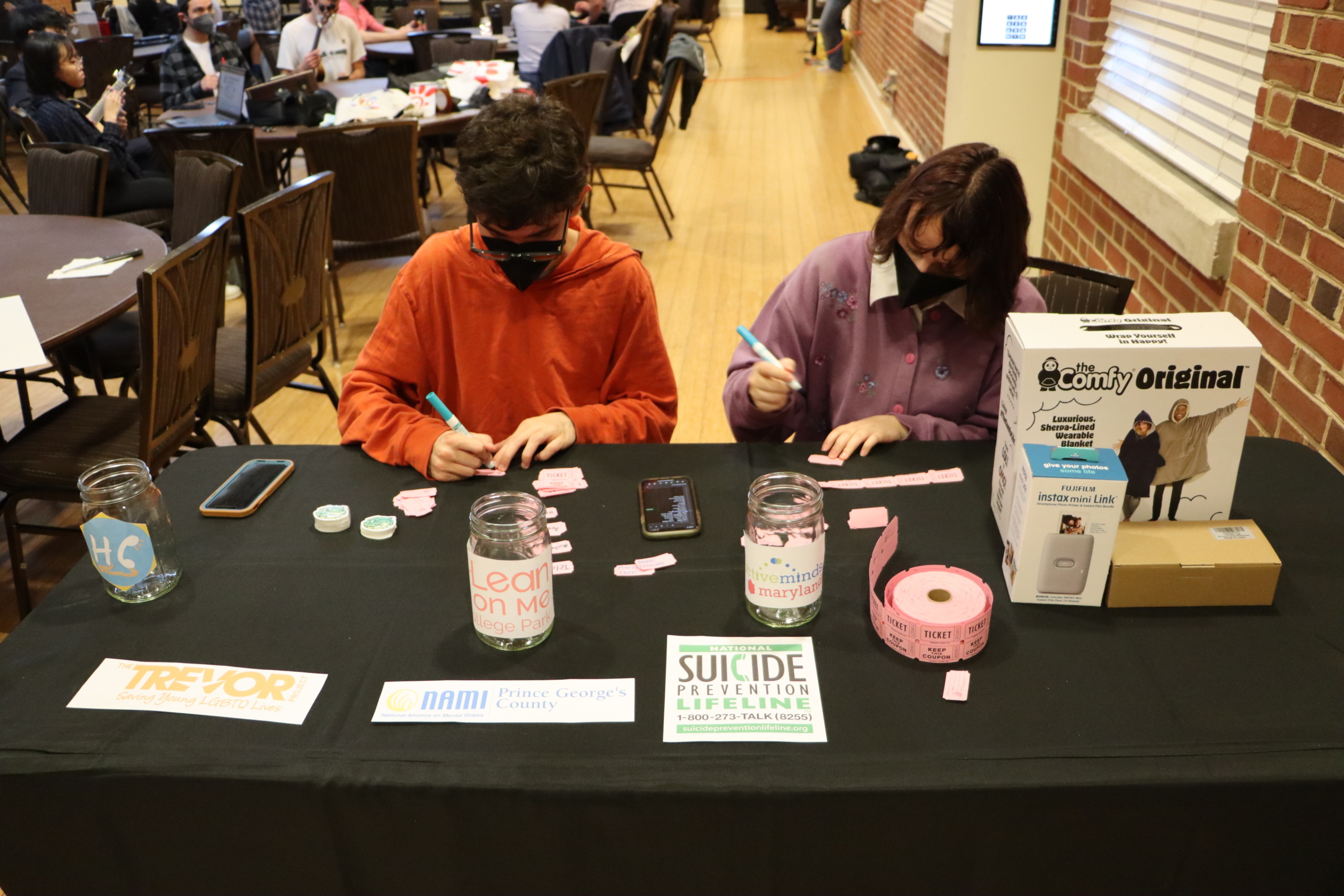

The approachability of students, as opposed to formal counselors, is key to the success of peer services. In 2020, current senior Tesia Shi founded a chapter of Lean on Me, a non-profit establishing mental health peer text lines at colleges nationwide and another organization highlighted in MCI’s paper, at the University of Maryland College Park (UMD). As she carved out a space for the group on campus, Tesia said she was conscious to avoid projecting an image that could seem too “corporate.” It was important to clarify that the text line volunteers would have unique personal experience to understand both student- and campus-specific challenges. “We are trained, and we are competent,” she explained. “But we’re just another student.”

The relatability factor also poses to break down barriers to care for students who might not view their problems as serious enough for professional help, feel wary of therapy or had a bad experience with university counseling center. “It’s not necessarily something where you would go to a therapist and start a whole therapeutic relationship over, but it still bothers you,” Tesia said of the reasons UMD students might text Lean on Me. “And over time, if things like that build up, it can turn into something worse. So we’re trying to target the prevention side of things to offer an outlet for people to talk about those more daily, common things.”

It’s not just the students who receive support that stand to gain from peer-to-peer work. Dolores Cimini said research suggests peer support can also help providers with their behavioral, affective and emotional development, and Amanda is a testament to that effect. “It helps me with my recovery, helps me with my mental health, just by helping others,” Amanda said. Even when her work between Middle Earth and the Collegiate Recovery Program begins to weigh on her, she feels she can rely on their support systems. “They push us, but they’re also there for us. So it’s a great balance of having responsibility but also recognizing that we’re human and that we’re also an undergrad.”

Still, if the role of peer support in a public health approach to the youth mental health crisis is anecdotally apparent, more concrete evidence remains to be so. “The practice of peer support lacks common definitions, some level of standardization and a substantial body of research showing efficacy across these programs,” Zoe Ragouzeos said of MCI’s findings during the webinar. “The burning question ultimately is: Which type of peer support programs will help with which types of students with which types of problems?”

So, what’s next? MCI recommends the world of higher education invest in solidifying definitions of the different types of support, including peer education, listening, support groups, coaching, and counseling; standardizing how programs get assessed to make them easier to compare; developing research-informed regulations and best practices; and improving these best practices for each peer support type. For colleges and universities, MCI suggests integrating peer support programs into broader wellness plans and connecting with students leading these groups, whether they’re officially tied to the school or not.

These efforts to establish definitions, standardization, and university oversight could help tackle the safety concerns currently limiting peer support. For Amanda, coordinating with UAlbany faculty and staff was simple, thanks to their long-standing relationship with Middle Earth. Tesia, on the other hand, struggled to launch Lean on Me in the face of some administrative humps. “It was really, really hard, and I’m pretty sure there’s still some doubts even now,” she said. “When we were working together with our counseling center, their reaction was kind of like, ‘Who are you to be doing this? Are you qualified?’ They were really worried that we weren’t going to be actually helping students—that we would be making things worse.”

“I know that university initiatives and policies can move very slowly. So everything needs to be super, super solid before it’s implemented or approved,” Tesia added. “But I sense that part of the reluctance might just purely be because it’s something new.” She said she imagines the unfamiliarity of the texting modality helped fuel skepticism.

Acknowledging the uncertainty that comes along with them, Amanda believes peer support programs are worth it. “Risk is definitely something that every university should take into account to make sure they’re protecting students on both sides. However, if that’s the reason that you’re just completely canceling it out as even an option, I wouldn’t necessarily agree with that because students are struggling, especially post-pandemic,” she said. She emphasized peer support as an important resource for those students still put off by the stigma surrounding traditional help-seeking. “I’d like to say that it really does save lives.”

That’s not to say that student leaders are against systemizing policies and practices, as long as they come by a thoughtful process. “I think having a basic blueprint to get your foot in the door, if that’s what the university needs in order to get going, is awesome,” Amanda said. “But every university looks different, so I think it’s also important to know what your university really needs and prioritize that throughout the process.” Tesia agreed, saying that standards are important to ensure quality programming, but student autonomy has its merits, too. “I wouldn’t want schools to take it over and then not have students be the driving voice or force behind it.”

In the end, the schools and students occupied by peer support may just be “on the same side,” Tesia said. “I think it comes out of a deep desire to make sure that students are getting the best.”