The pandemic wreaked havoc on the favored tactics used by student organizers — but also created pockets of innovation

A month before COVID descended, early 2020 was already a time of acute upheaval at Brigham Young University.

In February, the administration had decided to erase the edict against “homosexual behavior” from its Honor Code, a move celebrated by LGBTQ+ students and their supporters. Then in March, the university clarified – some would say reversed – its decision, confirming its alignment with the teachings of the Church of Latter-Day Saints. “Same-sex romantic behavior cannot lead to eternal marriage,” wrote the commissioner of the Church Educational System, “and is therefore not compatible with the principles included in the Honor Code.”

Hundreds of students gathered with colorful signs in front of the student union, day after day. “There was a mood,” one organizer told the Salt Lake Tribune, “like wanting to stay at this until they recognize that we’re part of this community and we’re not going to go away. Just this desire to keep going and keep trying until we’re heard.”

Then came COVID. And for all the wanting to stay, there would be no ability to keep going. Students masked, classes moved online, and campus activism evaporated.

“Students had been quick to organize about the Honor Code, but it was right before COVID,” said Sarah Sherren, a senior at the time. “So when classes were canceled, it was like all that was shut down, too, and the movement and momentum they created stopped right away. It was a shame.” Though she describes herself as “not so much” of an activist, Sherren wrote an article for BestColleges.com about the palpable change in campus energy, engagement, and mental health, and “diminished quality discussions.”

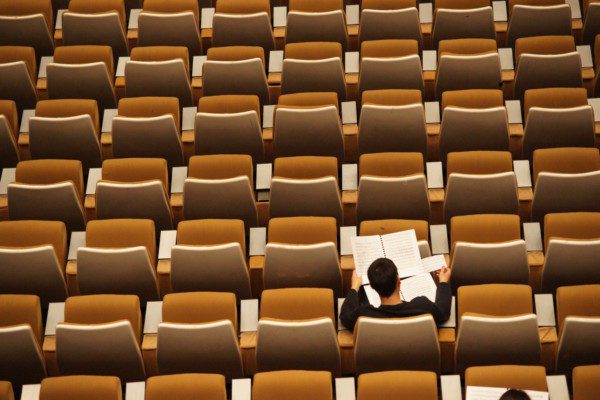

“I enjoy seeing what people are up to. I want to hear what people are doing and thinking. I like to be in the know,” she said. “It’s a big issue and a lot of students are struggling with this. But suddenly everyone was masked, and no one wanted to speak as much, or sit, talk, and engage. You kept to yourself. It did feel quieter, and lonely.”

Welcome to student activism in the age of COVID. The pivot that many universities made from in-class to remote learning had a muffling effect on the usual ways students would speak out, generate supporters, and catch administrators’ attention. Nearly overnight, the possibility of gathering in crowds was ghosted. When the ordinary rhythms of student life broke down, the physical distance and isolation took their toll on the unified aspect of shared passion for a cause. Some of the energy dissipated – or at least became diffused, amorphous.

It’s not unusual to find college students engaged in political activism. But the pandemic –combined with BLM and the 2020 election – appears to have generated a deeper level of political engagement.

“Just getting new members is harder for these students when you can’t meet in person,” said Markie Pasternak, manager of impact and engagement for Active Minds, a nationwide organization dedicated to mental health in higher education. “Newer chapters might lose their leadership with a graduating class, and it becomes rudderless without students on campus.”

Kelly Maguire, a senior at Florida Gulf Coast University, watched that happen at the school she’d attended before FGCU. She was president of the chapter she and her friends had founded at Florida SouthWestern State College. “After COVID, graduates left and underclassmen scattered around the country. We’d spent all our free time establishing that group from nothing, building it to winning a national award. But after everyone left during the pandemic, students didn’t really know what the group was all about or how to keep it going. It was really defeating to watch.”

But just as traditional protest modes shut down, students’ passion for public expression lit up with social justice issues and political divisiveness raging within the pandemic’s wake. Modes of expression adapted, and in some cases, so did students’ technological sophistication. They might not have been able to stand with megaphones on a quad, handing out pamphlets, or seize an administrative building. But they seized familiar tools – digital tools of social media they’d come of age with. They also learned new ones, like digital ads and geofencing, online town halls and text banking.

“The country was sorting out health concerns, but that didn’t stop students from coming together for George Floyd and BLM and other issues. The drive to support these things seemed so strong they superseded public health rules. They felt they couldn’t take a pause because these issues were bigger than themselves,” said Will Meek, Global Director of Mental Health & Wellness at Minerva University, and during the first wave of COVID, Director of Counseling & Psychological Services at Brown University. “For many of these students, their primary identity is as organizers, and activism for social justice is the main driver of their life. Fortunately for them, this happened in a time of the greatest sophistication of digital tools we’ve ever known.”

After COVID descended, BYU students struggled to find new ways to protest, but ultimately found them. Instagram posts about the Honor Code controversy created campus buzz, and “car rallies” took the place of in-person protests during BLM. When students wanted to launch a pro-masking public health campaign, they created a website and used social media digital ads, as well as billboards throughout the city, essentially geofencing their message.

Similar innovation was happening on campuses across the country:

*A student at Yale – a poet and member of the Navajo Nation – began using her literary Instagram platform to raise awareness of the high rates of COVID on reservations. The response rate skyrocketed. “Usually what I post doesn’t get a lot of response,” said Kinsale Hueston, “but now because people have been kicked off campus and they have to go online in this specific scenario, they’re looking for these opportunities to learn.”

*At Michigan State University, members of the Asian, Pacific Islander and Desi American (APIDA) student community hosted an online town hall pressing for changes in a range of areas to achieve greater equity, and had a turnout of more than 300 people, including administrators.

*During the George Floyd protests, a student at John Jay College of Criminal Justice researched data on political contributions, and publicized information about a surprising number of New York City progressives receiving donations from conservative police unions. He tweeted what he’d found and it went viral; some politicians responded to public pressure by donating funds to racial justice organizations.

*At Auburn University, members of Active Minds had formerly handed out buttons with information and sayings as a way to generate awareness and make contact with people on the concourse. That level of contact wasn’t allowed during COVID, so they attached buttons to a bulletin board in the student center – new buttons every week with clever sayings that became conversation-starters and collectibles.

It’s not unusual to find college students engaged in political activism. But the pandemic –combined with BLM and the 2020 election – appears to have generated a deeper level of political engagement. A Gallup poll conducted with Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life in 2020 found that 79% of young people say, “the coronavirus pandemic has helped them realize how much political leaders’ decisions impact their lives.” It also appears to have helped them realize ways they can get engaged in the process – not just read and talk about it.

At Brown and the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), students in the Providence chapter of the Sunrise Movement for climate justice engaged in phone banking and text banking, tactics typically associated with professional political campaigns. Another group at Brown, Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere (HOPE), has been working to provide tenants at risk of eviction with declaration forms from the CDC to use as shields against eviction if they are covered by the CDC’s temporary eviction moratorium. And then HOPE upped its game, submitting written testimony supporting a bill that would prevent landlords from discriminating against tenants receiving housing assistance.

COVID certainly isn’t the first time students have used legal measures to enact change. But the pandemic closed off traditional avenues of physical protests and raised the stakes, so students became particularly dexterous at speaking the legal language of the forces they were working to change.

At Boston College in May 2021, members of the group Climate Justice were planning a demonstration. They felt their voices weren’t being heard by the administration on divesting in fossil fuels. They intended to convene at an off-campus park popular for gatherings, masked and six feet apart, in line with the school’s COVID rules. But they did not register the protest with the university, which was also part of the university’s policy. When the school learned about the event three hours before it was to happen, Climate Justice was warned it could lose its status as an official student organization.

“They approved a much smaller demonstration on campus during finals, not something anyone would really attend. We decided there were other ways to get our message across,” said a then-senior student organizer, Kyle Rosenthal. “We’d already hit a critical mass of acceptance that divesting was the way to go, with 85% of students and faculty voting in favor, so we didn’t need to reach that audience. We had to reach the decision-makers, the press, and public opinion. We really dug into the social media strategy commenting on every tweet BC made, tying everything they posted back to the environment, and how they were really hurting it by not divesting.”

They were noticed, and Climate Justice also hosted a town hall-style webinar. But digital methods had their limitations. Zoom meetings weren’t always attended, and emails could be ignored. So in December 2020, a group of alumni, students, and others filed a complaint with the Attorney General of Massachusetts, arguing that Boston College trustees had violated their fiduciary duty by refusing to divest college endowment funds from fossil fuel companies. It’s a tactic other institutions around the country have used, and activists at Harvard University followed suit shortly afterward. Harvard announced its decision to divest its estimated $838 million before the Attorney General’s office completed its investigation; Boston College has not.

Much has been said about the negative effects of the pandemic on student motivation, but some university faculty and administrators saw resourcefulness and innovation and were not surprised.

“Everyone said students were going to be lost, and the staff would have to play chess with them online. I said, ‘Leave them alone. They’re going to come up with something way better than we can,’” said Meek. “They know how to do this. One of the character traits of activists is they figure out how to pivot and strategize better than anyone can. They deal with challenges, and find an opportunity to reach new audiences and fundraise differently. That’s just what they do.”

And while this is not a time anyone would have wished for, there have been lessons learned and work-arounds created that will last beyond the pandemic. Take Earth Day, for example. The usual youth presence in April was replaced with a 72-hour live-streamed “digital march,” with protests and speeches, attended by more than 200,000 viewers. Successes like this show a technique that’s more valuable than merely a back-up plan.

“I’d certainly say we have a greater open-mindedness to strategies that was driven by COVID,” says Morgan Whitten, a Harvard senior involved in the climate movement and divestment efforts. “Initially we tried to do virtual rallies, which we realized weren’t going to be effective, because you have to sign into a Zoom meeting and take part – it’s not like you’re walking by on the way to class and stop to look and listen. Administrators are not likely to see you if you’re not outside their building, and similarly, the media.” So, the group’s tactics shifted, and the complaint was filed with the Attorney General. “It was a pretty novel strategy that we think did convince the administration to decide to divest. And it’s entirely possible our group wouldn’t have taken that step if we were able to spend our efforts outdoors, in person, as we always have.”

Boston College senior Sophia Shieh saw the use of technology as an excellent bridge across different campus organizations and to administrators, pointing to the success of webinars and virtual peer drop-in groups. “By collaborating with many student groups, we could have conversations about race and mental health, and have a counselor talk from a clinical perspective how to integrate antiracism work into practice. We could talk about our institutional response to larger social issues, other protests, and hate crimes around the Boston area, and have a dialogue with administrators who participated too,” said Shieh. “These are definitely difficult conversations to have, but we were glad to be able to have them in spite of COVID. And since it was in a virtual space, people could access it from everywhere, and it was even livestreamed on Facebook.”

While COVID certainly wreaked havoc with so much of the way students expressed activism – along with how they lived, attended classes, studied, ate, exercised, and pretty much did anything – there were pockets of innovation, too. COVID might have been a story of struggle, but it has also been a time of adaptation and growth.

“There are elements of this, that if we’re painting this time with the brush of, ‘It’s so awful,’ then we’re missing part of the story,” said Meek. “A lot of people came through and found a way to continue. That’s incredible. They found a way.”